ABLE

Sandra Alland

PDF of this Piece // PDF of Issue 5

ABSTRACT: In “Able,” Sandra Alland uses stop-motion photography and recorded voice to create a metaphoric and literal vision of barriers to access. The text mixes Alland’s poetry with benefits/welfare applications, border control terminology, and medical and blood donor questionnaires. The hundreds of photographs feature thousands of steps and hills throughout Alland’s current home of Edinburgh, Scotland. The piece examines how disabled bodies move (or don’t move) through non-disabled space and time. Notions of race, class, gender identity and sexuality also intersect to ask the question: Who gets to be “able”? Featured in Tracey Moberly’s Tweet-Me-Up 2012 at Tate Modern (London).

Notes on “Able” and Accessible Filmmaking

As a disabled and low-income artist, I work diligently to make my artworks as accessible as possible to as many people as possible. My own physical and financial limitations have been a challenge in relation to filmmaking, and it is also sometimes difficult to balance the artistic intention of a work with various (and sometimes competing) forms of access. There has definitely been a learning curve during my collaborations with other disabled and/or D/deaf [1] artists over the past 15 years.

“Able,” my fifth short, is an example of my earliest film work. The audio is audible but rough, recorded in 2005 with a $10 microphone that I used with early-stage dictation software I bought to help with chronic pain. I shot the photos in 2010 on a fairly crap non-SLR digital camera. I was just learning how to use film-editing software, and because of lack of money I only had access to the most basic of programs. I had not studied filmmaking, and pretty much had no idea what I was doing. Editing hundreds of photos into “Able” was a painstaking, and painful, endeavour.

So the process was, and still is, slow.

There are many ways in which this film is not accessible. Although blind people can listen to the audio track of the poem, there is no audio description (AD) of the visuals in the piece. This accessibility issue could be potentially remedied with a voice-over at the beginning describing the action of the film, as well as descriptions during parts when there is no other important sound. Arguably, this addition might detract from the piece artistically (for example, by overshadowing the sound of breathing in the non-speaking sections). Then again, had I included a voiceover from the inception of the work, it probably would not have detracted much at all. I am working towards this kind of fully-integrated access in my current projects.

For a cinema screening, though, I usually create separate AD soundtracks, so blind and visually impaired people can listen to them through headsets (in cinemas thus equipped). Online it is more common to offer two versions of a film, one with AD and one without. I have this option for some of my films, and I could potentially work to create an AD soundtrack for this film, should my health and financial situation allow at some point.

“Able” also does not have closed captioning. Instead, I created basic subtitles (or open captioning) for the piece. When I made “Able,” I was starting to learn about the conventions of captioning, so I did manage to include some descriptions of sounds, instead of merely subtitling speech in the film. However, I failed to format the descriptions properly. For example, I put the description of the sound of breathing in parentheses, using “(breathing)” instead of “[BREATHING].” There are different formatting conventions in different countries (varying somewhat between Canada and the United Kingdom), but usually descriptions of sounds are in italics or are in capital letters or bracketed capital letters. Most D/deaf viewers who are familiar with English would be able to follow along regardless, but my captions are less clear. Also, all the captions of spoken text should be in italics to represent that the voice is coming from off-camera (though this is fairly obvious because there is no recognizable “speaker” onscreen). To be honest, it is a miracle I figured out how to make captions at all back then, but I would definitely change them now if I could.

I also did not phonetically or textually describe the parts of the poem that are abstract or more sound-based. For example, I wrote “(strange rhythmic vowel sounds)” instead of, for example, “Ah. Eee-ay. Ah-oo.” I have struggled with this decision at screenings of the film, still unsure how I feel about it. Many D/deaf and/or neurodivergent [2] viewers might in fact find the second (more accurate) choice less useful than the first. Users of sign language in particular would not necessarily be familiar with the concept of onomatopoeic words, with which hearing or hard-of-hearing viewers would likely be familiar.

I made this decision for two reasons: I wanted to avoid the potential confusion of spelled-out sound poetry for a D/deaf audience, and I also did not necessarily want to give away or spell out how the abstracted sounds of the poem were constructed. I wanted the viewer/listener to struggle (along with me) to figure it out and to experience the sound collage cumulatively throughout the piece. For example, writing out “Hv y bn t Wst frc” after the viewer has seen the words “Have you been to West Africa?” is more obvious than when you only hear the consonants without the vowels (it is more difficult and abstract in sound than in writing).

This sound aspect of the piece can arguably be best experienced by hearing viewers, as abstract sound is perhaps inherently inaccessible to profoundly deaf people. There are times when artistic “vision” and full accessibility are at odds with one another, and I have had many productive discussions with other disabled and D/deaf artists about how to best achieve the desired result when this tension occurs. I feel I could improve the captioned descriptions of my sound poetry, but I am not yet sure precisely how.

I am sadly also unable to make any visual changes at all. I no longer have the original file without captions. This film stands instead as a testament to my development as a disabled artist and activist, at a point when ideas were first starting to come together for me. Fail better next time!

What else? In this film the subtitles are large, and white with a black outline. I now make all my captions slightly smaller so they are less distracting, and in pale yellow with a black outline. Yellow stands out far better and is also preferred by some people with different visual needs.

Of course, captioning is not a solution for many D/deaf people. There are D/deaf people who use only sign language. Whenever I host or perform at events, I have interpreters present for live performances and discussions. In addition, I have made two films with a Deaf poet, Alison Smith, that feature sign language, captions and some lip-speaking. However, “Able” unfortunately does not yet have sign language or lip-speaking versions available.

I am thrilled to engage in dialogue with people knowledgeable and passionate about access. These are exciting times, as creating disabled and D/deaf access in film is becoming more accessible to broke and disabled filmmakers like me, indeed to everyone. There are more and more brilliant projects that involve integrated and creative access from their inception.

Below I have included an in-progress transcript of the film/poem, for those who are interested, including D/deaf and/or neurodivergent viewers who may want a text version. It contains a more detailed account of the sound poetry, in which I give some clues to the source of the sounds, but try not to give too many. Perhaps these descriptions would make for better captions; making them has certainly helped me think through how a sound piece might be transcribed for D/deaf and/or neurodivergent viewers in the future. Thanks for watching and/or listening.

—Sandra Alland, Edinburgh, August 2015

Notes

1. “D/deaf” is an abbreviation for “Deaf and deaf.” The adjective or noun,“deaf” usually refers to the physical state of “not-hearing.” It can include people who are “hard of hearing,” a term used to describe those who do not hear well or who have lost some or all hearing later in life. When capitalized, “Deaf” is a cultural (and often political) indicator. BSL/ASL-users, and people who view themselves as part of a Deaf community and distinct language-based culture, are more likely to use “Deaf.” Such people do not equate deafness with disability.“

2. Neurodivergent, sometimes abbreviated as ND, means having a brain that functions in ways that diverge significantly from the dominant societal standards of “normal.” Neurodivergent is quite a broad term. Neurodivergence can be largely or entirely genetic and innate, or it can be largely or entirely produced by brain-altering experience, or some combination of the two (autism and dyslexia are examples of innate forms of neurodivergence, while alterations in brain functioning caused by such things as trauma, long-term meditation practice, or heavy usage of psychedelic drugs are examples of forms of neurodivergence produced through experience).” -Nick Walker

Able

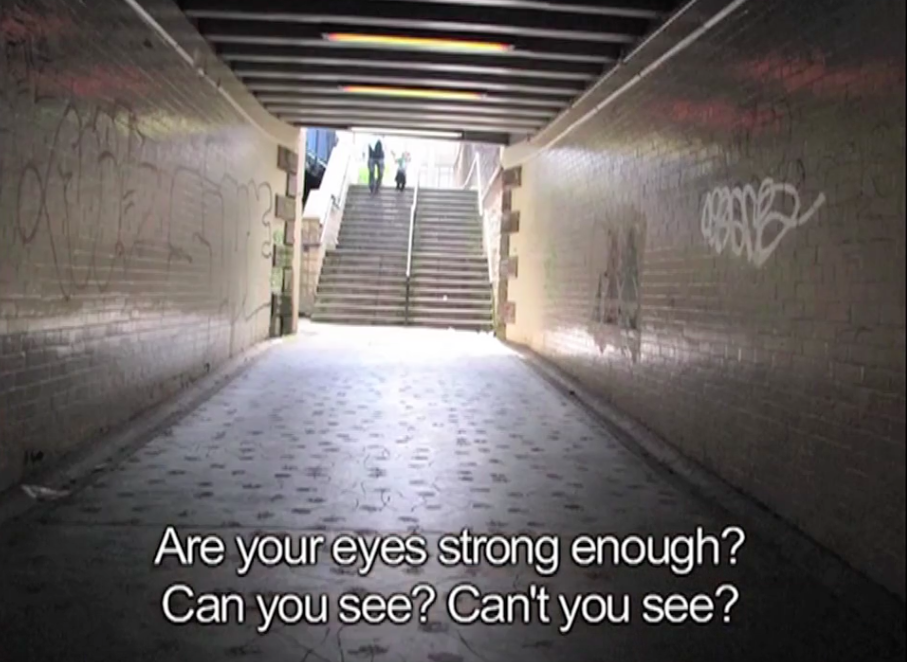

The film features stop-motion colour photography from the filmmaker’s perspective behind the camera, climbing and descending many stairs and hills throughout the city of Edinburgh, Scotland. The cuts between photos are rhythmic, and often in time to the recorded poem. Most photos are visible for a second or less. There are many people in the photos; most overtake the filmmaker as the camera goes up and down hills. Some moments stand out: someone leans down to give money to a person sitting on the ground; a musician plays guitar all alone high up on a staircase; shadows and tourists’ feet land on dirty streets with mostly gorgeous architecture. At one point in the middle of the film, when the voice says “Escucha,” (subtitled onscreen as “Escucha/Listen”), the screen goes black for several seconds of silence. The images resume with the sound of breathing, and the spoken poem continues to move along with photos of stairs, hills and people. Near the end of the film, the voice speaks faster and the images change faster. With the final spoken word, “Respira” (subtitled onscreen as “Respira/Breathe”), the final image appears: a blue sky with white clouds. It fades to black in silence.

1/

(This part of the poem is a sort of sound poetry: it features seemingly abstract sounds, in this case using only vowels. Later in the poem there are parts with only consonants, as well as more vowel-only sections. The sounds are rhythmic, fairly staccato, and of variable speed. But first, the sound of slow, rhythmic breathing. This breathing continues for the entire poem, except during the blackout, and despite never changing it gives the impression of being more and more tired.)

Aw. Oo-ay. Ah-oo.

Aw. Oo-ay.

Aw. Oh-I. Aw-eh-uh.

Ahh. Oo-eee. Ah-oo-ee. Aw.

Oo-ee. Oh. Ah. Ih.

Ay-eh-ih. Ow. Oh.

Ah-uh. Ih-oh. Ee-eh. Ah-oooooo.

(Breathing.)

2/

Are you able?

Can you?

Are you able?

Are your eyes strong enough?

Can you see?

Can’t you see?

I meant without glasses.

Lift. Hold. Resist.

Hmmm.

Can’t you?

Make a fist.

Run run run. And jump.

Hmmm.

I don’t see a problem.

Are you eating well?

Do you smoke?

Have you ever smoked?

Ah.

(Breathing.)

3/

Do you have any of the following symptoms?

sadness irritability indigestion

nausea fear embarrassment

Do you feel tired? Horny? Hungry? Do you eat to feel better? Do you eat?

How much do you weigh?

Really.

Are you currently or have you ever been depressed?

Attracted to women?

Hmmm.

Do you have piercings? Tattoos?

Have you ever slept with a man who slept with another man?

Have you ever had sex with a West African?

Have you been to West Africa? Are you African?

Ah.

(Breathing.)

Respira. Respira, mi amor.

(Breathe. Breathe, my love.)

Respira. (Breathe.)

Escucha. (Listen.)

(Silence.)

4/

Is anyone in your family

dying of cancer

prone to accidents

a communist?

Have you ever been on welfare?

Where did you get those shoes? Do your feet hurt?

How tall are you? Can you orgasm?

And lift. Reach up. And down.

Circle the one that does not belong.

Can you?

(Breathing.)

5/

Do you hear voices?

T-t-t-tr. Cc-t. D-t. Wmn?

Hmmmm-ah.

Hv. Yi. Vr. Slpt. Wth mn

Respira, mi amor. Respira.

(Breathe, my love. Breathe.)

nthr mn?

Respira. Escucha.

(Breathe. Listen.)

Hv yi vr hd ss-kkk-sss wth Wst frcn?

Hv. Vv. Yy. Vr. Bn. Wst frc-k?

Drink? Hmmm. Drugs? Really. Suicide?

Ah.

Take two of these in the morning

and ten of these at night.

Regular heart rate

periods

bowels

church?

(Breathing.)

6/

Where do you think the pain is?

Does this hurt? This?

Hmmm.

Have you ever had an STD? an RRSP?

been to a protest?

declared bankruptcy?

Male or female?

Married or single?

On the pill?

I suggest the pill.

Do you eat meat?

I suggest meat.

Acne?

Headaches?

Menstrual pain?

Jewish?

(Breathing.)

7/

Tell me what this is.

Ay. Ah-eh-uh-uh. Ah-uh.

Uh-uh-uh. Ah-uh.

Ay-oh-ee-ah-aw-uh.

Aw. Oo-ee. Ih-uh. Oo-oo-oh.

Ah. Oo-eheh-oh. Oo-eheh-oh.

Ah.

And this.

Rrr. Rrr. Yy. Yy. Frcn. Frcn. Frcn. Frcn.

Dd yy hv ny pr cccc ngs.

Tttt-ssssssss. Tttt-sssssssss. Tttt-sssssssss.

Really. Do you have insurance?

(Breathing.)

8/

It’s got to come off. It’s got to come out. We’ve got to go in. Take a number. Roll up your sleeves. Take off your shoes. Raise your arms. Empty your pockets. Join that line. Remove your belt. Spread your legs. Open your mouth. Bite. Swallow. Spit. Your thumb. Turn. Cough. Breathe. Hold. Blow.

Respira. (Breathe.)

Sandra Alland is a Scottish-Canadian writer, filmmaker and interdisciplinary artist. Sandra’s films have screened internationally, including at Tate Modern, Glasgow Gallery of Modern Art, Together! Disability Film Festival (London), San Francisco Transgender Film Festival and Entzaubert (Berlin). Sandra was awarded The LitVid Prize (Canada, 2012), bpNichol Award (Canada, 2013), and a Cultural Commission to mentor D/deaf and disabled queer and trans filmmakers (UK National Lottery, 2013). She is co-editor on a forthcoming anthology of UK disability poetry (Nine Arches Press). Visit her website: www.blissfultimes.ca