ON ASSUMPTIVE SOLIDARITIES IN COMPARATIVE SETTLER COLONIALISMS

Dana M. Olwan

PDF of this Piece // PDF of Issue 4

ABSTRACT: On December 23, 2012, a large group of Palestinians from occupied Palestine and diasporic Palestinians from the settler-colonial states of Canada and the United States issued a statement in support of the Idle No More Movement and Indigenous rights to sovereignty and self-determination. This article explores the assumptions and politics of solidarity that inform this statement and what they reveal about the current historical conjuncture of alliance and coalition-building amongst Palestinian and Indigenous people. By pointing to shared histories of settler colonialism between Indigenous peoples and Palestinians, it situates alliance politics within a broader context of critical relatedness, mutuality, and reciprocity. It thus explores what assumptive relationship between these two peoples has meant for movements and struggles against the settler-colonial state of Canada and what type of challenges this interpretive and political framework may pose to anti-colonial pursuits that seek to create more just worlds across varying but interconnected contexts of occupation, coloniality, and settlement.

Introduction

On December 23, 2012, a large group of Palestinians from occupied Palestine and diasporic Palestinians from the settler-colonial states of Canada and the United States issued a statement in support of the Idle No More Movement and Indigenous rights to sovereignty and self-determination. [1] The statement, circulated repeatedly on pro-Palestinian and anti-Palestinian websites, blogs, and news sites, asserts the following:

Indigenous people have risen up across Canada in the Idle No More movement, a mass call for Indigenous sovereignty, self-determination and rights, against colonization, racism, injustice, and oppression. As Palestinians, who struggle against settler colonialism, occupation and apartheid in our homeland and for the right of Palestinian refugees–the majority of our people–to return to our homeland, we stand in solidarity with the Idle No More movement of Indigenous peoples and its call for justice, dignity, decolonization and protection of the land, waters and resources. (“Palestinians in Solidarity,” 2012)

In addition to its support of Indigenous struggles against colonization and oppression, the statement recognizes the “deep connections and similarities between our peoples,” including our shared histories of genocide and ethnic cleansing. Urging us all to “idle no more,” from Turtle Island to Palestine, the statement resonated with various community activists, organizations, and academics.

Emerging from a very local Canadian context of targeted legislative attacks on Indigenous governance and sovereignty, the Idle No More movement was shaped in response to Canada’s past and ongoing legacy of the colonization of Indigenous lands, lives, and bodies. This movement offers an alternative to the vision of economic extraction and environmental destruction driving Canadian state interest in and utilization of Indigenous lands. Idle No More, as Anishinaabe scholar Leanne Simpson (2013) tells us, “is [an] alternative [that is based in] deep reciprocity. It’s respect, it’s relationship, it’s responsibility, and it’s local.” Through multi-pronged cultural, rhetorical, and political strategies, the movement confronts exclusionary state policies and practices while reimagining Canada’s borders and boundaries and the state’s relationship to Indigenous people. Linking a critique of global capitalism with a contestation of settler colonialism, Idle No More teaches us about decolonization at a time of war and empire. As a movement encompassing a series of acts, Idle No More contests conditions of colonialism and occupation while highlighting how these conditions structure the daily lives of Indigenous people across a variety of spaces. The movement thus brings our attention to the situated contexts in which oppression becomes articulated and resisted and so compels us to understand our collusions with and contestations of hegemonic powers, both of settlement and coloniality, and our differential roles in these processes.

As a Palestinian residing in the United States and an immigrant of color to Canada, I support Idle No More and endorse the Palestinian statement’s message of solidarity with Indigenous people and its resolute support of Chief Theresa Spence’s courageous hunger strike. The urgency of the statement of support, and its demand that Palestinians take action against the ravages of colonialism and occupation on this continent, resonate well beyond the boundaries of the Canadian state and thus carry an important message about the possibilities of decoloniality. Almost three years after its publication, and as a signatory to its message, this statement and its undergirding conceptions of solidarity continue to simultaneously inspire and trouble me. In this paper, I explore the assumptions and politics that inform this statement and what they reveal about the current historical conjuncture of alliance and coalition building amongst Palestinian and Indigenous people. By pointing to the shared and simultaneously varied histories of settler colonialism between Indigenous peoples and Palestinians, I situate alliance politics within a broader context of critical relatedness, mutuality, and reciprocity. In particular, I am interested in examining what the implied (and sometimes even stated) natural or assumptive relationship between these two peoples has meant for movements and struggles against the settler-colonial state of Canada and what type of challenges this interpretive and political framework may pose to our anti-colonial pursuits as feminists committed to creating more just worlds across varying but interconnected contexts of occupation, coloniality, and settlement.

As I will argue, the underlying logic of this statement is instructive because it reveals both the limits and possibilities of solidarity as a politically essential framework for mobilizations and struggles. In addition to turning to this particular historical moment of alliances between Palestinian and Indigenous peoples, I explore an example of queer resistance to state inclusions and migrant justice work in the shadow of the Canadian settler-colonial state. Drawing on feminist and queer theorizations of alliance politics, I rethink what it means to rely on assumptive solidarities or likely alliances between and amongst Indigenous peoples across disparate—yet interrelated—temporal, historical, and geopolitical contexts. In other words, I want to think about alternative visions of solidarity that are not, in the words of Rubén A. Gaztambide-Fernández (2012), “simply about entering into a state of solidarity—to be in solidarity—which might suggest feelings towards, but about actions taken in relationship to someone” (54; emphasis in original). By looking at separate but connected instances of solidarity, I argue for the importance of moving towards an understanding of solidarity that does not conceptualize innocence or sameness as prerequisites for liberation movements and justice struggles, and that challenges assumptions of mutuality and commensurability between different settler-colonial contexts.

Connecting Indigenous Solidarities

The Palestinian statement of alliance with Idle No More was the result of serious efforts by Palestinian and Indigenous activists in Canada to create historical and material linkages between our struggles. As evidence from activist researchers shows, solidarity work amongst Palestinian and Indigenous peoples is not a recent phenomenon but can be seen as early as 1970s with the establishment of a formal working relationship between the Canada Palestine Solidarity Network and the Native Study Group, both members of the Third World Peoples Coalition (Krebs and Olwan 2012). With the passing of time, such co-operations have not vanished or ended but have, in fact, been strengthened and renewed by the re-articulation of the Palestinian struggle through a comparative settler-colonial lens, as evidenced in the works of various students activist organizations in Canada, including Solidarity for Palestinian Human Rights (SPHR), the Coalition Against Israeli Apartheid (CAIA), and Students Against Israeli Apartheid (SAIA). Campaigns to raise consciousness about the mutuality of Palestinian and Indigenous struggles are not exclusive to university campuses but have also transcended the confines of the ivory tower, often highlighting these links in public spaces. Importantly, this work has also included support for Indigenous confrontations against past and ongoing state theft of Indigenous lands and resources, such as the Six Nations Lands Reclamation Struggles in 2006. This truncated historical account is worth exploring in order to better understand the different forms of solidarity and alliance that has existed between Indigenous and Palestinian people in Canada. Such research can help challenge romanticized accounts of solidarity that gloss over power asymmetries. While recognizing the importance of this task, this article does not delineate this history and focuses, instead, recent forms of Palestinian solidarity activisms that centre around the Idle No More movements.

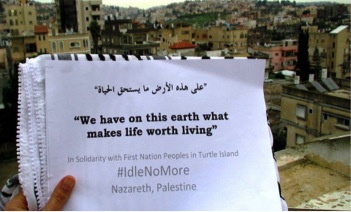

During the height of Idle No More activisms, Palestinians enduring Israel’s policies of ethnic cleansing and its geographies of dispossession and displacement posted messages of solidarity with Indigenous people through Twitter and Facebook. Citing the late Mahmoud Darwish, one note read: “We have on this earth what makes life worth living,” a message of solidarity from Nazareth, Palestine.

Picture taken in Nazareth by Nayrouz A.H.

In an interview about the deepening connections between Palestinians and Indigenous people in the wake of the Idle No More movement, Stó:lō author and activist Lee Maracle has noted that, although solidarities have existed for decades, this movement has “‘crystalized’ the relationship” even further (Ditmar 2013).

Solidarity work between Indigenous people and Palestinians, while present for decades and largely transformative in its goals and politics, has also struggled with some organizational and structural difficulties that are worth exploring to discuss more carefully and honestly the past and ongoing relationships of alliance and network building. As Palestinian organizing around the Six Nations Lands Reclamation Struggles in 2006 reveals, mobilization efforts in support of Indigenous people often function through the imperative of crisis and its logic of management (Krebs and Olwan 2012). Rather than creating long term, sustainable, and ongoing relationships of solidarity, crisis management as short-term solidarity inhibits possibilities for transformative solidarities. Similarly, efforts by pro-Palestinian student and activist organizations to involve Indigenous people in pro-Palestinian work taking place on Indigenous lands often do not envision Indigenous activists as empowered decision-makers within such groups. Instead, Indigenous people and their struggles for self-determination and sovereignty are sometimes tokenized at the personal, organizational, structural, and systemic levels.

More alarmingly still, some pro-Palestinian groups also replicate the ways in which settler-colonial states use Indigenous people and their cultures to fulfill performative acknowledgments of occupied lands and resources. This tokenism includes incidences where Indigenous activists are invited to provide opening ceremonies for pro-Palestinian events that sometimes do not integrate a critique and explicit challenge of Canadian and United States settler coloniality and thus normalize the violence of such states. This type of activism renders invisible what Dene scholar Glen Coulthard (2007) has described as the “profoundly asymmetrical and non–reciprocal forms of recognition either imposed on or granted to [indigenous] people by the colonial-state and society” (6; emphasis in original). In other words, they repeat a settler-colonial logic that conceives of indigeneity in terms that are both familiar and nonthreatening and that serve to strengthen non-reciprocal and hierarchical colonial relationships.

Taken collectively, what do these disparate and truncated accounts of solidarity and its difficulties reveal? Furthermore, how do these narratives structure relationships between Indigenous and Palestinian people in Canada and beyond? To address these two questions, I will return briefly to the Palestinian message of solidarity in support of Idle No More. Although this message performs the important political function of showcasing Palestinian support for Indigenous rights, it also recasts this particular Indigenous moment—which has its roots within the historical realities of land treaties, resource theft, and expropriation as they relate to Canadian state policies and practices—through the analytical lens of the Palestinian struggle. As its authors write in response to the Canadian government’s record of support to the Israeli state:

[Stephen] Harper [Canada’s Prime Minister] and his government’s expansive praise for Israeli settler colonialism and apartheid is simply the other side of the same coin that attacks Indigenous self determination and plans massive resource extraction on Indigenous land. (“Palestinians in Solidarity,” 2012)

While this claim may be true, how does this analysis—which aims at expanding our critique of settler colonialism and recognizing its interconnected local and global manifestations—end up narrowing its scope and minimizing its power? How does this lens end up emphasizing ahistorical commonality and mutuality to the detriment of historicized differences and distinctiveness? In this statement, we see how sometimes divergent Indigenous and Palestinian concerns are distilled into singular, indistinguishable, and uniform sites of mutual struggle and resistance. In the genuine desire to find solidarity between and amongst our peoples, we often unconsciously disappear the particularities of one another’s histories. In this context, an overreliance on assumptions of inherent relationality, mutuality, and connection lends credence to what Zainab Amadahy refers to as the unwillingness and inability of the Palestinian solidarity movement to “interrogate the complexities of settler colonialism on Turtle Island” (2013).

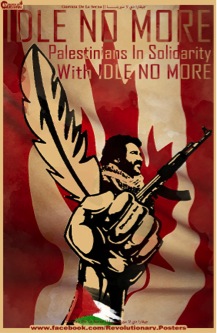

A move away from interrogating such complicities is also evident in the image that accompanied the Palestinian statement in support of Idle No More. In this figure, we see an activist wearing a checkered Kuffieh who stands behind a fist that holds a gun and a feather—an image that is meant to couple Palestinian and Indigenous struggles in imaginative and political ways. All are set against a backdrop of the Canadian flag. Here, the Canadian flag represents the Canadian state. Importantly, this image powerfully foregrounds the Idle No More movements and reasserts Palestinian support with it. Here, both struggles are presented as one and the same and both are tied together by imagery that points to the Canadian state’s complicities in shaping the colonial and oppressive realities of both peoples. While the Canadian state is certainly responsible for the legacies and conditions of coloniality under which Indigenous people live and die, is the Palestinian struggle shaped by the same realities or relationship to this state? Asking this question does not deny the importance of this image or its message. Rather it seeks to point to the limits of a commensurate framework of solidarity that inadvertently disappears differences between oppressed and colonized.

Poster accompanying Palestinian statement of solidarity with Idle No More. Designed by Guevara De La Serna.

Although a relational framework of solidarity helps us recognize similarities and mutualities in struggles, it also runs the risk of disappearing the particularities and specificities of settler-colonial states and the regimes of violence they enact against Indigenous peoples. How do we read for overlaps between the Israeli occupation of Palestine, the settler colonial systems in Canada and the United States, and the gendered violence against Indigenous people that such states produce in each of these contexts? What sort of framework is needed to consider these seemingly different spaces as interconnected, without losing an analysis of the specificity of violence in each case? How do we theorize the struggles for sovereignty of Indigenous and Palestinian peoples and what connections do we draw between different people’s struggles for different bodies, lands, and resources? To address these questions, I examine another instance of collective organizing and activism in recent years against the settler-colonial state of Canada: queer activism for migrant justice and against queer inclusion by the nation-state.

Im/Possible Alliances in the Shadow of the Settler State

On September 24, 2012, a large group of queer Canadians were surprised to find in their inboxes an email from the office of Jason Kenney, then Canadian minister of Citizenship, Immigration, and Multiculturalism. Addressed to the minister’s queer “Friends,” the mass email lauds Canada’s foreign policy and reminds queer Canadians of the state’s commitment to “take a stand against the persecution of gays and lesbians, and against the marginalization of women in many societies” (CBC News 2012). Among other national accomplishments listed in the letter, the Minister highlights Canada’s leading role in resettling Iranian queer refugees who have fled, in his words, “often violent lives in Iran, to begin new and safe lives in Canada” (Ibid). The mass email, which was neither issued in response to a letter by self-identified queers, nor collectively solicited by migrant groups concerned with the national or global status of LGBTQ or women’s rights, perplexed its recipients who could not comprehend how the state had determined or ascertained their queerness. An article in Xtra, a mainstream queer Canadian newspaper, asked, “Has Immigration Minister Jason Kenney been emailing you? Maybe it’s because you’re gay” (Ling 2012).

As activists and scholars have shown, queer rights—like women’s rights before them (and in tandem with them)—have become indices of state sovereignty and power. In this context, the Minister’s letter and its exclusive focus on the LGBTQ rights of queer Iranians recuperate Canada’s reality of settler colonialism and advance, instead, an image of a welcoming and migrant-friendly host nation-state. While Muslim communities in Canada continue to be targeted for state surveillance and control, Canadian state practices invite queer asylum seekers to trade on “Muslim sexuality” and the War on Terror for fleeting assurances of inclusion and belonging (Puar 2011). In what follows, I use Kenney’s letter and the response it has solicited from queer activists and allies as an entry point into a broader discussion about the possibilities and limits of national and transnational solidarity work in queer and non-queer contexts. Specifically, I am interested in addressing a question posed by Shaista Patel about how our strategies of resistance and solidarity can “[challenge] the violence of occupation in the white settler colony of Canada and in other spaces” (2013). This evidence of state-sponsored pinkwashing speaks to the specific ways in which Canadian settler colonialism is reinscribed on and by queer bodies and spaces. I use this story to extend my discussion of solidarity politics in settler-colonial contexts and to showcase the ways in which solidarity politics are not only messy and complicated but also how they become differently formed and articulated in the geographies of occupation and settler coloniality. The previous sections have highlighted the trouble with a too-easy reliance on histories of similarity and alliance; this section extends this discussion to raise questions about queer activisms in settler-colonial nation-states.

Issued two weeks after Canada’s severance of diplomatic relations with Iran and its formal listing as a state sponsor of terrorism under the Justice for Victims of Terrorism Act (2012), Kenney’s letter demonstrates how targeted, regulated, and sometimes outlawed sexualities become intertwined with official national state agendas and politics. In this context, the inclusion of queer migrants evidences Western states’ inherent goodness, openness, and generosity, and their willingness to fulfill what Sarah Lamble (2013) describes as the promise of “greater safety, security, and vitality to (worthy) sexual citizens” (233).

In 2002, this illusory promise of security was granted to some queers when the Canadian state provided formal recognition to non-married “same sex” and opposite sex couples for purposes of immigration sponsorship. Under the amended Immigration and Refugee Act, queer couples in “good faith” relationships could file for Canadian citizenship if able to render legible to the state their queer bodies, identities, and practices. To be extended the state’s protection and concomitant citizenship rights, queer asylum seekers fleeing gender or sexual persecution became compelled to provide discursive, material, and physical evidence authenticating their homosexuality to Canadian decision makers. In this Western fantasy of queer life, predicated on what Palestinian queer activists from Al-Qaws have termed the “politics of visibility” (Hilal 2013), queer migrants become known to the Canadian state precisely through its capacity to liberate and then violently incorporate them into its national rhetorics.

For many migrants, failure to provide proof of sexual marginality and deviance before arrival to Canada is tantamount to death. Take, for example, the story of Leatitia Nanziri, a self-described lesbian from Uganda, whom Canadian officials were prepared to deport because the Immigration Review Board did not perceive her account to have “the aura of a genuine recounting of actual events and experiences” (quoted in Justin Ling 2012). In violently discounting Nanziri’s sexual identity, the board argued that they did not have sufficient evidence that demonstrated that she had ever been in intimate relationships with women. Having been raped repeatedly by state officials for her suspected homosexuality, Nanziri had not engaged in visibly public or definitively “out” lesbian activities that could evidence her queerness. As such, Canadian officials did not consider her a worthy subject of queer inclusion and sexual asylum.

To understand why some queers (and some women) come to occupy a central place in Canadian discourse, one needs to consider the historical context in which the bodies of nationalized queers are regularly used to assert state superiority and extend techniques of border management and control. As Anna Agenthengelou (2013) has recently argued, “sovereign worlding power is inconceivable without a legal and moral obligation to one’s queers as well as the larger international community’s queers” (454). Rather than view this instrumentalization of queer bodies primarily at the discursive or affective levels, it is important to note that the selective and opportunistic state interest in queer inclusions has already charted a new Canadian racial and sexual landscape that is most clearly evidenced in current migration policies and practices.

While the government can trumpet its cooperation with the Iranian Railroad for Queer Refugees and use the admittance to Canada of 150 queer Iranian asylum seekers in the past four years as a shield against charges of Islamophobia, migration-justice activists cannot overlook the fact that such inclusions have coincided with increased incarcerations and deportations that amount to more than 7,500 removals of failed refugee claimants in 2013 alone. This number includes the “voluntary” removal of Victoria Ordu and Favour Amadi, two Nigerian students at the University of Regina deported by Canadian officials for the crime of working off campus without proper permits. Here, stories of queer Iranian and Muslim inclusions like the ones touted by the Canadian state mask the anti-Blackness propelling unjust immigration policies regularly articulated on the bodies of Black migrants in white Canada.

Thus, to celebrate stories of inclusion, one must willfully ignore how they are defined by the increased shift from permanent settlement to precarious and temporary belonging for a majority of peoples. As migration-justice groups such as No One is Illegal have shown, the Conservative government has adopted harsher family reunification measures and introduced a two-year “conditional” permanent resident status for the sponsored partners and spouses of immigrants and Canadian citizens. Under the guise of fiscal responsibility, the government has also cut federal health refugee programs and lowered the salaries of temporary migrant workers. Together, these migration policies do not simply usher new or unusually precarious forms of belonging but also enshrine racial and sexual differences at the national level.

To their credit, some queer migrant groups and activists in Canada have responded creatively and provactively to exercises of state violence, cooptation, and manipulation such as the one exemplified in the Minister’s unsolicited and self-congratulatory email. While various queer organizations focused their criticism of Kenney’s email on state surveillance of queer bodies and its incursion on personal privacy and sexual freedoms, the response of queer migrant groups struck a different chord, one that is explicitly inspired by emergent and growing critiques of queer inclusion. Refusing to be made complicit in a state-sponsored practice of pinkwashing that seeks to conceal Canada’s hawkish policies towards Iran, the authors of the letter condemned the Minister for his attempt to “instrumentally highlight the homophobia faced by LGBT people” (Various 2012). Respondents opposed the racism inherent in Canadian immigration policies that jeopardize the lives of both queer and straight asylum seekers from around the globe. Reminding the Minister that the targeted migrants are “friends, lovers, family […] and community members” (ibid), the statement focuses its criticisms on Bill C-31, a bill which has granted the Minister of Citizenship the right to refuse asylum applications from “bogus” refugee claimants and determine asylum eligibility based on country of origin. This dissident response reveals the power of a queer “counter-public” that takes up “racism and war as queer issues” and thus refuses, in the words of Jin Haritaworn (2012), to “loyally repeat the nation” (75).

The refusal of queer activists and allies to participate in a politics of solidarity that re-centers the nation-sate provides insights into the dangers of queer organizing that works to obscure or deny sexual imbrications in national inclusion projects. As Michael Connors Jackman and Nishant Upadhyay explore in an important article on the reification of the white settler nation-state in queer movements in Canada, “non-Native queer movements can naturalize settlement and colonialism and claim normative and national queer citizenship” (2014, 200). Or, as Scott Morgensen writes, “In this moment of engaging solidarity, thinking queerly can highlight how our acts articulate many forms of coloniality” (2015, 310). Against this backdrop and history of colonial forms of queer movements, the above-cited example of queer activisms against the settler-colonial state of Canada can offer hopeful insights into a radical queer critique and the promise of global solidarity in the face of what feminist scholar Sunera Thobani (2002) labels “war frenzy” (5). However, it also raises important concerns regarding the elision of settler-colonial critique and resistance from queer purview. In stating this point, I do not seek to absolve myself from such criticism, nor do I wish to participate in what Mary Louise Fellows and Sherene Razack (1998) have aptly called the “race to innocence” (335). Rather, I am interested in exploring the politics of queer resistance to state incorporations. If the very founding of the Canadian state is predicated upon the dual process of appropriation of Indigenous lands and resources and the consolidation of racist immigration policies that target Black people and people of color, how can a critique of queer inclusion decouple itself from a critique of settler colonialism? How can we speak of violence against queer migrants in the Canadian context without speaking of colonial violence against Indigenous and Black bodies—queer and straight? How can we confront the violence of queer inclusion without resisting the violences of genocide, dispossession, elimination, and exclusion that structure the daily realities of Indigenous life in Canada today?

While I am unable to provide definitive responses to the questions that I raise here, inherent in them is the belief that the struggles for Indigenous sovereignty, migrant justice, and anti-colonial activisms are interlinked. In this political moment, queer and Palestinian activisms against state inclusions in Canada—and elsewhere in North America—require attending to the complexities and complicities of settler colonialism in ways that might have the potential to be, as Harsha Walia (2013) argues, “transformative, healing, and revolutionary” (276). This example, then, compels us to question the ways in which alliance and solidarity politics can work to dismantle the very structures and capacities of the settler-colonial state that seduce, lure, and imbricate. Rather than suggest that this work is easy or clear-cut, I use this evidence of queer activism at a critical national juncture to point to the ways in which refusals of queer inclusion must be understood in relation to, and not just in opposition with, the very structures of colonial powers they may ultimately wish to dismantle. As such, solidarity work is necessarily relational, demanding that we concede our imbrications in colonial webs of domination and resistance. Queer activisms in settler-colonial contexts—such as Palestinian activisms and solidarity efforts with Indigenous people in Canada and the United States—must not be situated in a framework that too readily assumes marginalization and innocence as building blocks for liberatory movements. Instead, activism must always concede complex power differentials amongst groups whose struggles, though intertwined, might also diverge. I thus return to an examination of Palestinian and Indigenous solidarities to offer ways to think through the complicated geographies of alliance politics and their critical potentials and limitations in struggles against settler-colonial states.

The Seductions of Solidarity

In 2013, Ryan Bellerose, self-identified Zionist Métis Native-rights activist, penned a strongly worded op-ed in which he rejected the assumption of a shared history between Indigenous and Palestinian people. He wrote the article, “A Native and a Zionist,” was written in response to the Palestinian statement in solidarity with Idle No More. Bellerose argues against the “co-opting of today’s native struggle to the Palestinian propaganda war” and he refuses to “allow the Palestinians to gain credibility at our expense by claiming commonality with us” (2013). Widely circulated on Zionist and pro-Israel sites, Bellerose’s letter eschews Indigenous alliance with Palestinians in favour of solidarity with Israelis. Bellerose writes that the “The Palestinians are not like us. Their fight is not our fight” (2013). To convey just how different Palestinians are from Indigenous people, Bellerose reminds us that Palestinians did not become dispossessed through systematic colonization “but [had] lost the land they want by waging a needless war on Israel” and that they “persistently refused peace overtures and chose war” (2013). Rather than dismiss this account as the ravings of a fringe right-wing individual, I want to urge solidarity activists and academics to pay attention to the uncomfortable and even mainstream questions Bellerose raises about the politics of assumptive alliance and solidarity. Namely, if alliance between Indigenous people and Palestinians is neither divinely ordained nor biologically scripted, what are the specific tools through which this much needed solidarity could be sought, built, and fostered?

An instance that illuminates this point is Palestinian and Indigenous contestation of Native American poet and activist Joy Harjo’s visit to Israel. In spite of numerous appeals by many Indigenous scholars—including Robert Warrior, Director of American Indian Studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and activist scholar J. Kēhaulani Kauanui—Joy Harjo broke the Palestinian issued call for Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions when she chose to receive funds and perform at Tel Aviv University. In response to her critics, Harjo promised to visit Ramallah and meet with Palestinians living under Israeli occupation in the West Bank. Harjo’s act revealed an unwillingness to heed calls for solidarity and betrayed an inability to understand the far-reaching consequences of her individual actions on a fellow colonized people. Palestinians who wrote against Harjo’s visit recounted how, growing up in occupied Palestine, they learned about Indigenous people and their struggles, finding connections with Native Americans. Others wrote of their grief and sense of betrayal at Harjo’s refusal to heed the boycott and recognize the similarities between Native American and Palestinian struggles (Al Atshan 2012; Abu Nimah 2012).

These responses can rest on assumptions of shared and common struggles and expectations of Indigenous solidarity that sometimes elude reciprocity. This logic reveals much about the dangers of comparative settler-colonial frameworks and affective solidarity politics, especially ones that rely on emotional connections instead of working through political alliance and support in mutual and reciprocal ways. If Palestinians assume affinity with Indigenous people, does it necessarily follow that Indigenous people must feel that way about us too? In asking these questions, I seek neither to demonize nor trivialize the positions taken by fellow activists and scholars in highlighting Harjo’s act and its meaning for Indigenous peoples. Rather, I am interested in interrogating the uses of a settler-colonial framework in comparative contexts of colonial subjugation and Indigenous resistance and the ways in which such a framework can sometimes create expectations and assumptions of solidarity and that are not always based on reciprocal and relational work.

Although a settler-colonial framework helps us recognize similarities and mutualities in struggles, it also runs the risk of disappearing the particularities and specificities of settler-colonial states and the regimes of violence they enact on Indigenous peoples. Settler-colonial critique opens up the possibility of recognizing this fact, and thus can play a large part in shaping mobilizations against personal and collective forms of violence across a variety of national and international contexts. Writing on the advantages of a settler-colonial analytical framework and critique in a recent issue of the Journal of a Settler Colonial Studies, Omar Salamanca, Mezna Qato, Kareem Rabie, and Sobhi Samour (2013) remind us that a comparative settler-colonial framework is useful precisely because “[i]t brings Israel into comparison with cases such as South Africa, Rhodesia and French-Algeria, and earlier settler colonial formations such as the United States, Canada or Australia, rather than the contemporary European democracies to which Israel seeks comparison” (4). More importantly, though, Palestinian settler-colonial critique extends recognition of the “fact that Palestinians are an indigenous people” and thus this form of critique serves to “[align] Palestine scholarship with indigenous and native studies” (ibid).

Heeding the calls of Indigenous scholars in the United States and Canada reminds us that applying a settler-colonial critique and engaging in relational forms of solidarity—however consciously, ethically, or responsibly—do not exonerate us from responding to Indigenous calls for sovereignty and land reclamation or to confronting the complexities of genocide, ethnic cleansing, occupation, and colonialism in the settler-colonial states of Canada and the United States. Nor does theorizing settler-colonial links across disparate but interconnected geographies of gendered violence inculcate us from what Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang (2012) name as an analytical “fantasy that is invested in a settler futurity and dependent on the foreclosure of an indigenous furturity” (14). Based on their challenge to non-Indigenous “arrivants” and settlers, how can we enter this critique as a process with—rather than for—others who are engaged in potentially mutual, but possibly incommensurate, liberation struggles (Jodi Byrd 2011)?

To answer these questions, it is important to consider how a politics of solidarity—aiming to expand our recognition of the local workings of settler colonialism and its interconnected global manifestations—can end up emphasizing ahistorical commonality and mutuality to the detriment of historically situated differences and distinctiveness. Echoes of these questions have shaped solidarity efforts and analyses across various sites of solidarity. It cannot be assumed or given, but must be relational. It is developed by constantly challenging the politics of short- and long-term alliance and through reworking our relationships to one another in non-hierarchical and non-dominant ways. Writing on the politics of solidarity with Palestine, Lyn Darwich and Haneen Maikey invite us to recognize the importance of “invest[ing] in building proactive long-term strategies under the unifying vision of decolonization and liberation” (2014, 283). While Darwich and Maikey’s articles focuses on the liberation of Palestine from Israeli occupation, violence and colonialism, they are both clear that such decolonial struggles must be framed within “interconnected frameworks of homonationalism, cultural imperialism, and settler colonialism” (283). By paying attention to the interconnections between these frameworks and struggles, we might be able to dislodge or challenge assumptions of solidarity with Indigenous people that fail to interrogate our own relationships to histories of settler colonialism on this continent.

For pro-Palestinian activists committed to working towards solidarity with Indigenous peoples, such theorizations can help us reconceptualize our alliance politics in ways that are intimately informed by “sustained investigations of power itself” (Morgensen 313). Here it is useful to heed the words of Harsha Walia who reminds us that solidarity work requires “cultivating an ethic of responsibility within the Indigenous solidarity movement [which] begins with non-natives understanding ourselves as beneficiaries of the illegal settlement of Indigenous peoples’ land and unjust appropriation of Indigenous peoples’ resources and jurisdiction” (2012). In the case of Palestinians living in Canada, this work may often involve recognizing and confronting our own complicated positionalities as migrants who live on occupied Indigenous lands and who have, at times, been incorporated into the settler colonial state of Canada – however uncomfortably, unwillingly, or precariously. Rather than erase such recognitions from solidarity efforts, I suggest centering them by continually rejecting the promises of inclusion and illusions of belonging extended by the multicultural settler-colonial state.

To that end, this article argues against appeals to solidarity that rely too easily on assumed, rather than shared, connections between Indigenous, queer, and Palestinian struggles. Solidarity is easy; it requires no work, no engagement. Assumptive solidarity is romantic—allowing us to imagine allies in unimaginable and unlikely spaces and places. It is a form of solidarity that diminishes fears of our Others, rendering them same in our minds and hearts. Assumptive solidarity is dangerous, as it makes our allies’ causes and forms of resistance appear less foreign, less threatening, and less cumbersome. Assumptive solidarity does not move us; it moves others to us. It does not transform our relationships with one another or with the lands on which we live, nor does it require our sustained, long-term, and wide-ranging commitments to work that is, at times, difficult, uneasy, and complicated. This form of solidarity is comfortable; it is felt affectively but never experienced materially, situationally, or historically. While enticing, this form of solidarity does not move us closer to those whom we wish to be in alliance with, nor does it directly confront of transform the conditions under which we come to encounter one another. Instead of this model, I want to commit to working toward responsible, ethical, and mutual forms of solidarity that are historically situated and politically conscious. Those movements are built on relational understandings of one another’s past and current dreams and desires—ones that simultaneously recognize the potential mutualities and various incommensurabilities of struggles for justice against settler-colonial states.

Notes

1. For the full statement, see http://uspcn.org/2012/12/23/palestinians-in-solidarity-with-idle-no-more-and-indigenous-rights/

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to acknowledge the work and support of Shaista Patel, Nishant Upadhyay and Ghaida Moussa, the Guest Editors of this issue. The author also thanks Samantha Balzer and the Managing Editors of Feral Feminisms for their patience and professionalism. Finally, the author thanks the two anonymous reviewers for their generative and important comments and questions.

Works Cited

“Palestinians in Solidarity with Idle No More and Indigenous Rights.” US Palestinian Community Network. December 23, 2012. http://uspcn.org/2012/12/23/palestinians-in-solidarity-with-idle-no-more-and-indigenous-rights/

Agathengelou, Anna. “Neoliberal Geopolitical Order and Value: Queerness as a Speculative Economy and Anti-Blackness as Terror.” International Feminist Journal of Politics. 15, no. 4 (2013): 453-476.

Amadahy, Zainab. “Relationships Across Cornfields and Olive Groves.” Fuse Magazine. April 17, 2013. http://fusemagazine.org/2013/04/36-2_amadahy.

Abu Nimah, Ali. “Palestinian Trail of Tears: Strong Reactions to Joy Harjo’s Refusal to Boycott Israel.” Electronic Intifada. December 11, 2012. https://electronicintifada.net/blogs/ali-abunimah/palestinian-trail-tears-strong-reactions-joy-harjos-refusal-boycott-israel.

Al Atshan, Sa’ed. “Palestinian Trail of Tears: Joy Harjo’s Missed Opportunity for Indigenous Solidarity.” Indian Country Today. December 11, 2012. http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2012/12/11/palestinian-trail-tears-joy-harjos-missed-opportunity-indigenous-solidarity.

Bellerose, Ryan. “A Zionist and a Métis.” The Métropolitan. March 13, 2013. http://www.themetropolitain.ca/articles/view/1235.

Byrd, Jodi. The Transit of Empire: Indigenous Critiques of Colonialism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011.

CBC News. “Jason Kenney’s Mass Email to Gay and Lesbian Canadians.” CBC News. September 25, 2012. http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/jason-kenney-s-mass-email-to-gay-and-lesbian-canadians-1.1207144

Coulthard, Glen S. “Subjects of Empire: Indigenous Peoples and the ‘Politics of Recognition’ in Canada.” Contemporary Political Theory. 6, no. 4 (2007): 437-460.

Darwich, Lynn and Haneen Maikey. “The Road from Antipinkwashing Activism to the Decolonization of Palestine.” WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly. 42. 3-4 (Fall/Winter 2014): 281-285.

Ditmar, Hadani. “Palestinians and Canadian Natives Join Hands to Protest Colonization.” Haaretz. January 19, 2013. http://www.haaretz.com/news/features/palestinians-and-canadian-natives-join-hands-to-protest-colonization.premium-1.500057.

Fellows, Mary Louise and Sherene Razack. “The Race to Innocence: Confronting Hierarchical Relations Among Women.” Journal of Gender, Race, and Justice. 1 (1998): 335-352.

Gaztambide-Fernández, Rubén A. “Decolonization and the Pedagogy of Solidarity.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education, and Society. 1, no. 1 (2012): 42-67.

Haritaworn, Jin. “Women’s Rights, Gay Rights, and Anti-Muslim Racism in Europe.” European Journal of Women’s Studies. 19 (2012): 73-80.

Hilal, Ghaith. “Eight Questions Palestinian Queers are Tired of Hearing.” The Electronic Intifada. 27 November, 2013. http://electronicintifada.net/content/eight-questions-palestinian-queers-are-tired-hearing/12951.

Jackman, Michael Connors and Nishant Upadhyay. “Pinkwatching Israel, Whitewashing Canada: Queer (Settler) Politics and Indigenous Colonization in Canada.” WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly. 42. 3-4 (Fall/Winter): 195-210.

Klein, Naomi. “Dancing the World into Being: A Conversation with Idle No More’s Leanne Simpson.” Yes! Powerful Ideas, Practical Actions. March 5, 2013. http://www.yesmagazine.org/peace-justice/dancing-the-world-into-being-a-conversation-with-idle-no-more-leanne-simpson.

Krebs, Mike and Dana M. Olwan. “‘From Jerusalem to the Grand River, Our Struggles are One’: Challenging Canadian and Israeli Settler Colonialism.” Journal of Settler Colonial Studies 2, no. 2 (2012): 138-164.

Lamble, Sarah. “Queer Necropolitics and the Expanding Carceral State: Interrogating Sexual Investments in Punishment.” Law and Critique. 24. 3 (November 2013): 229-253.

Ling, Justin. “Jason Kenney’s Gay Email.” Daily Xtra. August 2, 2012. http://dailyxtra.com/canada/news/jason-kenneys-gay-email.

Morgensen, Scott L. “A Politics Not Yet Known: Imagining Relationality within Solidarity.” American Quarterly. 67.2 (June 2015): 309-315.

Patel, Shaista. “Rethinking Sexy Occupations: Critiquing Solidarity Limits of the Left in Canada.” Unpublished Paper. Critical Ethnic Studies Conference, Chicago. September 19-21, 2013.

Justice for Victims of Terrorism Act. March 13, 2012. http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/J-2.5/page-1.html

Puar, Jasbir. “Citation and Censorship: The Politics of Talking about the Sexual Politics of Israel.” Feminist Legal Studies. 19 (2011): 133-42.

Salamanca, Omar Jabry, Mezna Qato, Kareem Rabie, and Sobhi Samour. “Past is Present: Settler Colonialism in Palestine.” Journal of Settler Colonial Studies. 2, no. 1 (2012): 1-8.

Smith, Andrea. Native Americans and the Christian Right: The Gendered Politics of Unlikely Alliances. Durham: Duke University Press, 2008.

Thobani, Sunera. “War Frenzy.” Meridians. 2, no. 2 (2002): 289-297.

Tuck, Eve and K. Wayne Yang. “Decolonization is Not a Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education and Society. 1, no. 1 (2012): 1-40.

Various. “An Open Letter to Jason Kenney: We are not Fooled by Unsolicited, Self-Congratulatory Pinkwashing.” Rabble. September 24, 2012. http://rabble.ca/news/2012/09/open-letter-jason-kenney.

Walia, Harsha. “Decolonizing Together: Moving Beyond a Politics of Solidarity Towards a Practice of Decolonization.” Briarpatch Magazine. January 1, 2012. http://briarpatchmagazine.com/articles/view/decolonizing-together.

_____. Undoing Border Imperialism. Edinburgh: AK Press, 2013.

Dana M. Olwan is Assistant Professor of Women’s and Gender Studies at Syracuse University. A recipient of a Future Minority Studies postdoctoral fellowship, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Art/Research Grant, and a Palestinian American Research Council grant, Dana’s research is located at the nexus of feminist theorizations of gendered and sexual violence and solidarities across geopolitical and racial differences. Her work has appeared and is forthcoming in the Journal of Settler Colonial Studies; Canadian Journal of Sociology; Atlantis: Critical Studies in Gender, Culture and Social Justice; Feminist Formations; American Quarterly, and The Feminist Wire. She is currently working on her first book manuscript, Traveling Discourses: Gendered Violence and the Transnational Politics of the ‘Honor Crime.’