BODILY LOCO/MOTION: SEEING UN-/DISORDER, THE BODY, AND EMBODIED ARCHIVES IN EADWEARD MUYBRIDGE’S ANIMAL LOCOMOTION

Jessie Travis

PDF of this piece // PDF of Issue 1

ABSTRACT: “bodily loco/motion” interrogates the politics of representation, of seeing, and of being seen in the photographic archive. Sparked by an examination of Eadweard Muybridge’s Animal Locomotion series, this project begins to think through, make a space, and account for individual lived histories and embodied archives in discourses of the archive by mobilizing compositional agitation. After exploring discourses of archival “agitation,” the paper concludes with a discussion of my own attempt at intervening in the photographic archive and in a politics of archival representation through a piece of original artwork bearing the same title as this paper.

Two years ago, in the second semester of my PhD coursework year, I began working through both the theoretical and photographic elements of “bodily loco/motion.” A feminist, fat, queer studies scholar and disordered body, I was growing restless in an archive theory classroom dominated by conservative and traditional voices, which emanated from bodies that were validated, privileged, and prioritized in and by the “canonical” texts we were reading. As we traversed discursive ground from the likes of Vincent Kaufmann and Walter Benjamin, and from Georges Perec through to Jacques Derrida and Michel de Certeau, I asked, “What about the body? What about my body?” Week after week, I posed the questions: What do these theories—of walking or of drifting, for example—assume or presume about the body, and about its privileges and abilities? What of the absences of particular bodies or corporeal realities? I felt and still feel that these questions demand critical attention—a fact to which my colleagues in English 739: Archive and Everyday Life can grudgingly attest. Whether a mere photographic spectre, an offhand allusion, or an integral metaphor haphazardly cast aside in favour of grander postulations on art and life, the body and its very corporeal machinations—specifically eating, sleeping, and walking—seeped into and shadowed both the literature we were reading as well as my seminar’s weekly discussions. Yet, these assumed corporeal abilities remained as such: unacknowledged reminders of exclusionary ideologies of “normal” bodies (i.e., heteronormative, white, socioeconomically stable, able-bodied, “healthy”). From the able-bodied, drifting walks of the Surrealists to the unrealities of Henri Lefebvre’s real housewife to the “tortured” (Lefebvre 48) and “starving” bodies of Agamben’s Remnants of Auschwitz (Agamben 51), I wondered how we might begin to think through and account for individual lived histories and embodied archives in discourses of the archive and everyday life. I wondered how we might make space for embodied archives in the collision of the spectral bodies present in the rhetorics of the course material and the material bodies (e.g., bodies that leak, swell, ooze, burp, sneeze) having these discussions. After all, how can we fully comprehend the densities of city space or the rigid and restricting lines of cartographic authority without considering the assemblage of abilities, of histories, of life inscribed, scarred, stretched, written onto and into the very fleshy surfaces of the wandering, drifting, walking, writing, archiving, and everyday body? How do we account for the collision of or the rubbing against of these embodied archives with the everyday, with everyday archives, with other archives, and with the archives of others?

In both this paper and its companion visual piece, I explore the politics of representation in the archive by examining the insufficiencies of looking at bodies, of being seen, and of archiving this dynamic of seeing/being seen in archival studies as well as the institutional archive, such as the one housed in the McMaster Museum of Art. As my introductory remarks allude, the field of archival studies has been dominated by theoretical voices which privilege and reinscribe narratives of “normal”-bodiedness by speaking of, about, and around—as direct metaphor or allusion—a version of privileged corporeality. By being included in such institutionally validated spaces as “a canon,” these spectres are further concretized as markers of corporeal normalcy. It is specifically those bodies, which do not adhere to such ideologies of embodiment, that are rhetorically and metaphorically excluded from these canonical (i.e., institutional; archival) spaces. Take, for example, the malnourished (42), decaying bodies of Agamben’s “non-men” (44), “shell-m[e]n” (45), or Muselmanner. With their edema-swollen bodies, the Muselmanner are entirely embodied figures; in starvation and an existence tempered purely by the corporeal—they embody the body—the Muselmanner become “the complete witness (Agamben 47) and yet “have no story” (Agamben 44). The Muselmanner’s utter corporeality, specifically their leaking, swollen bodies of illness, denies them a space of articulating a self, of bearing witness in Agambenian rhetorics, and therefore of being archived. This paper focuses on the corporeal subject, and the institutional archive’s inability to represent the everyday, lived, fleshy realities and histories of that subject—or, rather, its resistance or choice to include or exclude certain realities. With a particular focus on the photographic archive, as well as the normalizing of the mechanized and “productive,” I turn first to what is, in many ways, one of the earliest attempts at archiving the body, Eadweard Muybridge’s Animal Locomotion series, before shifting gears into the disruption or reformulation of the photographic archive. As Robert McRuer asks, “What would happen if…we continually attempted to reconceive composing as that which produced agitation?” (49). After exploring discourses of archival “agitation,” this paper will conclude with a discussion of my own attempt at intervening in the photographic archive and in a politics of archival representation through the production of a piece of original artwork that shares a title with this essay. As a body “out of place, the one who does not belong” (Ahmed 2) in the classroom, the canon of archive theory, as well the medical and cultural archives of normal-bodiedness, I take my own body and its amassed, embodied archive as the subject of my work. “Allowing myself to remember,” to voice, to make visible, and to write my own un-orderly embodied archive into the larger corporal archival history functions as a “political reorientation” (Ahmed 2).

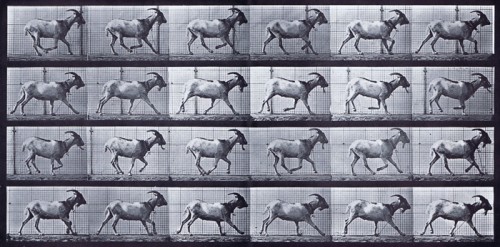

My corporeal questions or, rather, my search for the body in and embodiment of the archive, were never more acute nor more present than they were during a class field trip to the McMaster Archives, housed in the McMaster Museum of Art[1], where I first encountered Muybridge’s work. Commissioned by the University of Pennsylvania, the Animal Locomotion (1877-1878) series comprises 784 plates, each of which displays a set of motion-capture stills and breaks down the machinations of one, corporeal motion: “Goat galloping” (Figure 1); “Cricket, overarm bowling” (Figure 2); “Farmer using pick;” “Woman with cup;” and “Man boxing;” to name a few.

Figure 1:

Miller, Laurence. “Eadweard Muybridge.” Laurence Miller Gallery. http://www.laurencemillergallery. com/muybridge_animalLocomotion.htm

Figure 2:

Miller, Laurence. “Eadweard Muybridge.” Laurence Miller Gallery.

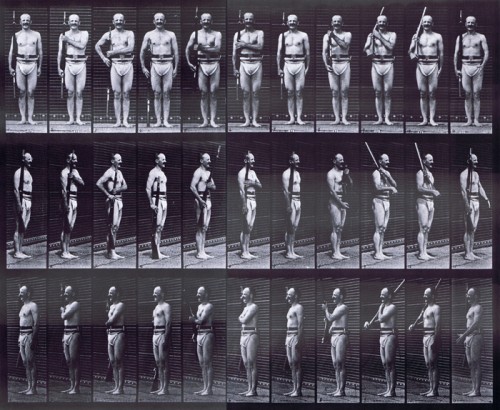

Of the plates housed in the McMaster Archives, it was “Man with shotgun” (Figure 3) that caught my eye.

Figure 3:

Miller, Laurence. “Eadweard Muybridge.” Laurence Miller Gallery.

Of Muybridge’s work, Tom Gunning writes:

Muybridge’s photography also makes visible a drama that would otherwise remain invisible: the physical body navigating this modern space of calculation. His images of the nude human body framed within a geometrically regular grid capture the transformations of modern life brought on by technological change and the new space/time they inaugurated, as naked flesh moving within a hard-edged, rational framework. (21)

If the act of photographing is simultaneously an act of making truth and an ideological engineering, as Alan Sekula, and to some extent, John Tagg explore, then what truths, what corporeal knowledge, does “Animal Locomotion”—its “hard-edged rational framework” hemming in and its ordering “naked flesh”—tell, stand in for, or create? In the act of archiving the body in locomotion; in forward moving and sequential advance; in an ordered, arching narrative of rectangular frames, what bodies are invited into the archive via Muybridge’s groundbreaking work? What bodies and bodily narratives are legitimated as orderly, productive, and normal in the act of archiving particular plates, for instance, and which bodies are excluded in the act of archival inclusion, remaining as merely 1 plate amidst 784, erased in their relegation to canonical absence?

In “Evidence, Truth and Order: Photographic Records and the Growth of the State,” John Tagg contests that the photograph’s penchant for the archive or to be archivable allows it to function as a harbinger of truth within a larger corpus demarcated as truth only by these very evidentiary enunciations. That is, the photograph can be largely decontextualized while still managing to support or validate certain and certain versions of history, which makes it a particularly desirable technology in the creation and cultivation of nationalist narratives. Because of its authenticating malleability, photography has been invested, since the turn of the 20th century, with “a power to see and record; a power of surveillance…[with] the power of the apparatuses of the local state which deploys it” (64). As such, photography is mobilized by political and governmental factions so as to manage and control shifts in economic, political, and cultural order and security. It is in the photograph, particularly those which are championed by institutional rhetorics as “normal,” then, that “we identify ourselves…Yet however carefully observed, the represented body is an abstracted body: the product of ideas that are culturally and historically specific, and in which the social formation of the producer determines the appearance and meanings of the body” (Callen 603).

In a particularly Foucauldian and biopolitical turn, then, those photographs that are validated, nay privileged, through the act of archiving become important technologies in the deployment of power as they organize, regulate, and manage bodies. Presenting an articulation of space and time that is “unified, standardized, and measurable” (Gunning 21), Muybridge uses photographic technology to break down the body and the its fluidity into a rigid and linear and mechanical narrative of forward motion; to order and flatten a complex and interconnected series of muscular, sensory, intellectual, and psychological actions; to quite literally look at the body as locomotion; as locomotive. If, as Anthea Callen supposes, “visual images are…potent mediators of the lived experience of the body,” Muybridge’s Locomotion series, particularly plates such as “Man with shotgun,” present and archive images of the weaponized and mechanized body, a body that is quite literally mobilized through the motion capture stills, as normal, “orderly,” and “docile” (Foucault 135). Perhaps even more so, “Man with shotgun” is a body that warrants a presence; a being seen; a space in the national archives and community as determined by its ability to adhere to heteronormative, race- and class-based articulations of masculinity.

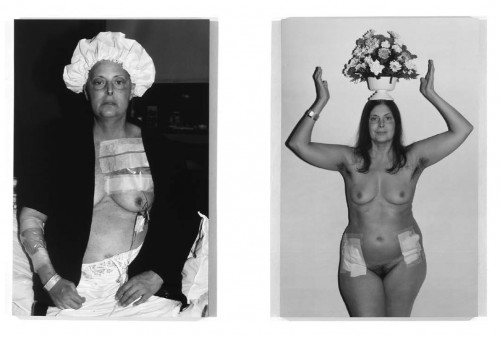

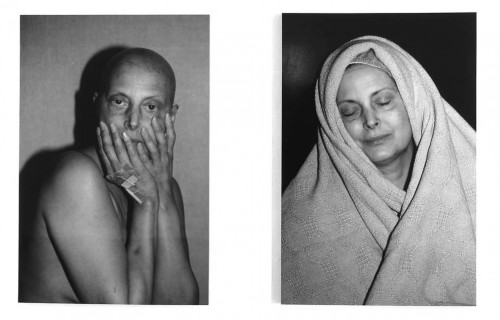

Through the form of the photographic composition, Muybridge evokes, as McRuer notes of other institutional forms of “ordering” and composing, “a cultural practice that would seem to be inescapably—even inevitably—connected to order. Webster’s Dictionary authoritatively defines ‘composition’ as a process that reduces difference, forms many ingredients into one substance, or even calms, settles, or frees from agitation” (48). Yet, by mobilizing the very medium, the very act of composing and of ordering from which institutions and archives derive power, other forms of visual practice and of photography—ulterior archives of photography perhaps—can create friction and agitation. For example, where the malnourished, leaking bodies of Agamben’s Muselmanner are, on account of their sickly, disorderly, and unproductive bodies, excluded from the act of bearing witness and of seeing and being seen, Hannah Wilke makes a critical space for re-imagining and re-narrativizing the passive, sick non-subject. Known for her long career as a feminist artist, Wilke brings her own cancer-ridden, scarred, shaped, and marked body into Art Historical conventions of beauty (Figures 4-5) by simultaneously rupturing narratives of the “ruined,” sick female body and the productive, “healthy” (and therefore “beautiful”) female body—narratives which are validated and maintained by the very archives that rely on and manufacture their disparateness.

Figure 4:

Tembeck, Tamar. “Exposed Wounds: The Photographic Autopathographies of Hannah Wilke and Jo Spence.”http://www.feldmangallery.com/media/wilke/ general%20press/Tembeck_RACAR.pdf

Figure 5:

Tembeck, Tamar. “Exposed Wounds: The Photographic Autopathographies of Hannah Wilke and Jo Spence.” http://www.feldmangallery.com/media/wilke/ general%20press/Tembeck_RACAR.pdf

Conventional pictorial narratives of illness seek to evoke sympathy from the viewer and shame in the viewed. In contrast, “while the artist is both socially and physically marked by illness, she reworks this inscription for herself through autopathography. In doing so, she provides a vehicle through which others can in turn reconsider their understandings of sickness and its impact on identity” (Tembeck 90). Likewise, Levin and Perrault argue that Nicole Jolicoeur’s work on nineteenth-century archives of women[2] “questions authorized epistemologies” by “troubl[ing] the archives she uses by collecting, disassembling, and recollecting, in different ways, what was once immobilized for preservation” (141).

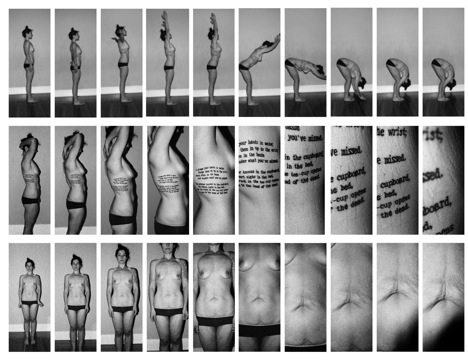

Like these other body artists before me, I recognize that “the body—as activist, as multiply identified, as a social enactment of a subject who is particularized beyond norms and stereotypes—plays a central role” and aim to scrape against, agitate, and unsettle these “norms and stereotypes” (Jones 697). Merely scratching the surface of culturally “absent” embodiments, my project looks to reconfigure Muybridge’s “locomotion” bodies, situating them within contemporary discourses of body weight and health (Figures 6-8). Bringing these Muybridge-inspired questions from the late 19th century and into my current cultural and ideological frame of reference, my own piece, entitled “archiv/ed: the body as archive/archiving the body,” explores what is left out of the photo-archived body. In Muybridge’s archive of “animal locomotion,” I argue that it is precisely the body itself that is absent in the archiving of its mechanics and its motion; in ordering and sequencing only the body’s productivity and actions and forgetting its mutability, its scarred, marred, and potentially unruly surfaces and interiorities, the series engineers and legitimizes particular discourses and ideologies of “normal” and “true” bodies through the act of archiving. While Muybridge’s men and women perform their minute actions, spread into staccato frames of captured motion, each of their bodies bears its own lived archive, an archive of sense, of feeling, of being embodied (Cvetkovich). This lived archive is an ever-present, ever-actualizing, everyday archive, which may or may not be antithetical, resistant, or in opposition to the impulse to mobilize, disembody, andmechanize the corporeal self. Nonetheless, it is absent from the photographs; therefore, it is abnormal or deviant.

My own piece (Figures 6-8) is comprised of three Muybridgean plates, printed onto plastic transparencies and suspended in front of a large-scale projected wall collage. In the first of my suspended compositions, I replicate a Muybridge plate as near to the original as possible. Where Muybridge’s “Man with shotgun” weaponizes corporeality, the mechanical actions of his body mirrored by those of his gun, my pictorial enacts North American discourses surrounding the healthy and productive body, as envisaged by paradigms of body weight and its associations with health. To this end, I take my own body as subject: I weigh within my culturally appropriate/acceptable weight range according to the Body Mass Index (BMI), which is culturally sanctioned as the indicator of normalcy and health. I am participating in class-based weight management activities (yoga) in my “leisure time” as a funded graduate student.

Yet, what underlies these actions, what is absent from the photographs of my “normal” body’s motions are deviant histories and unruly every days. A formerly “fat,”[3] fat and eating disordered,[4] disordered and underweight,[5] and culturally “normal” and disordered body, I bear these experiences with me every day, though these embodied histories are barely visible or unknowable to those whom I encounter and, for the most part, from the camera, photograph, and photographic archive. Just as my title upsets the very linear and etymological foundations of the archive by writing disorder or “ED” into the word “archive,” my proceeding compositions write both the surface of my everyday body and its embodied histories into the frames, previously allocated to the body’s movement, by bringing the lived body into the photographic archive.

Rather than tracing the body’s mechanical lurches forward, frame by frame, the second plate mobilizes the technological movement and the camera’s ability to shape, frame, and narrate the body by moving forward not the body but the camera. Where the first row maintains a Muybridgean locomotive aesthetic, the second and third rows differ, falling out of step. As the body remains static, the images zoom in on stretched and stretch-marked skin as well as their intersections with my own attempts to narrate, to mark, and to write my body through ulterior forms of scarring: in the instances pictured, tattooing; other inches of flesh reveal the thin, wisp-like etchings of self-mutilated cuts. Rewriting narratives of the “normal” body as indicative of and constituted by “health” and “order,” the final composite also diverges from a standard Muybridge composite in the second and third rows. Where “Goat galloping” or “Man with shotgun,” for example, capture different angles of the human and non-human body in motion, motions which give shape and order to—and are shaped and ordered by—the corporeal narratives signified by Muybridge’s captions, my plate is composed of a motion capture still of everyday eating disordered behaviours, specifically the purge, which quite literally shapes my own body. Capturing the motion of the toilet flushing following a purge episode, the toilet is a synechdoche for the behaviours and embodied histories that are not charted on my own body, which are largely imperceptible. “Though it may not visually portray” my body directly, the toilet in this instance “sufficiently encapsulates the perceived or intended attributes” of my embodied self (Oguibe 574).

Finally, where Muybridge’s piece posits finality and truth through the firm narrative arc of the body’s motion, each image closely and precisely situated one preceding the next, my archive of images does indeed stand alone, replicating some semblance of sequential, and therefore narrative, order—as disorderly and disruptive as they may be to the logics of Muybridge. However, printed on transparencies, my plates give way, and give sight to the embodied histories, specifically the deviant, unruly, and corpulent bodies that came before them. They make visible that which shaped, stretched, etched, and wrote upon my “locomotive” body. What were once minor etchings and slim lines of negative grid space in Animal Locomotion are now enunciated and haunted by a collage of my former corporeal experiences, my former “weight” lives, and my former weight-based identities and subjectivities. Hanging behind my trio of composite transparencies is a collage of photographs from my late childhood, through my teenage years, and into my early adulthood.[6] These images captured and represented both varying levels of cultural fatness as well as images of the ideological “normal” eating disordered body: the “emaciated body of the anorectic” (Bordo 2367). As Sekula reminds us, “the shock of montage, [or] when pictures from antagonistic categories are juxtaposed in a polemical and disorienting way” (445), has the potential to unearth mechanisms and investments of power underlying photography and the photographic archive by scraping against or rubbing together seemingly disparate or incongruous narratives or histories. In the case of my collage, the flurry of photographs enact a rubbing together, a joining, and a blurring of a history of embodied archives—a scraping against and weaving into one and another of inextricable and inextricably bound selves, identities, and subjectivities.

In sum, my own archival project aims to expose and trouble the staccato articulation of Muybridge’s mechanical, productive bodies by unearthing and exposing the un-productivity, the corporeal deviance, the excess, and the disorderliness that haunts my every day. More broadly, “archiv/ed” has begun the project of bringing attention, of illuminating archival gaps in the representation of embodied histories, which function as a means of making bodies disorderly, deviant, or abnormal quite simply through their very absence and lack of representation. By agitating, scraping, and rubbing against these archival discourses, this project calls for a new way of seeing, of being seen, and of showing the lived and everyday body.

Figure 6:

Figure 7:

Figure 8:

Works Cited

Ahmed, Sara. On Being Included: Racism and Diversity in Institutional Life. Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2012.

Agamben, Giorgio. Remnants of Auschwitz: The Witness and the Archive. Brooklyn, NY: Zone Books, 1999. Print.

Brophy, Sarah and Janice Hladki. “Cripping the Museum: Disability, Pedagogy, and a Video Art Exhibition.” Journal of Literary and Cultural Disability Studies. Forthcoming. 2013.

Bordo, Susan. “From Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body.” The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. Leitch, Vincent B. Ed. New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2001. 2362-2376. Print.

Callen, Anthea. “Ideal Masculinities: An anatomy of power”. The Visual Culture Reader: Second Edition. Mirzoeff, Nicholas. Ed. London and New York: Routledge, 2002. 603-616. Print.

Cvetkovich, Ann. An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures. Durham: Duke UP, 2003. Print.

de Certeau, Michel. The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008. Print.

Derrida, Jacques. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1995. Print.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Random House, 1995. Print.

Gunning, Tom. “Never Seen This Picture Before: Muybridge in Multiplicity.” The Cinematic. Campany, David. Ed. London: Whitechapel Ventures Ltd., 2007. 20-24. Print.

Kauffman, Vincent. “The Poetics of the Derive.” The Everyday. Johnstone, Stephen. Ed. London: Whitechapel Gallery Ventures, 2008. Print. 95-101.

Kirkland, Anna Rutherford and Jonathan M. Metzl. Against Health: How Health Became the New Morality. New York: NYU Press, 2010. Print.

Jones, Amelia. “Dispersed Subjects and the Demise of the ‘Individual’: 1990s bodies in/as art.” The Visual Culture Reader: Second Edition. Mirzoeff, Nicholas. Ed. London and New York: Routledge, 2002. 696-710. Print.

Lefebvre, Henri. “Clearing the Ground.” The Everyday. Johnstone, Stephen. Ed. London: Whitechapel Gallery Ventures, 2008. Print. 26-33.

Levin, Patricia and Jeanne Perrault. “ ‘The Camera Made Me Do It’: Nicole Jolicoeur, Female Identity and Troubling Archives.” The Archive: Documents of Contemporary Art. Merewether, Charles. Ed. London: Whitechapel Ventures Ltd., 2006. 139-142. Print.

McRuer, Robert. “Composing Bodies; or, De-Composition: Queer Theory, Disability Studies, and Alternative Corporealities.” JAC 24.1. 47-78. Online.

Muybridge, Eadweard. Animal Locomotion. 1872-1885.

Oguibe, Olu. “Photography and the Substance of the Image.” The Visual Culture Reader: Second Edition. Mirzoeff, Nicholas. Ed. London and New York: Routledge, 2002. 565-583. Print.

Perec, Georges. “The Street.” The Everyday. Johnstone, Stephen. Ed. London: Whitechapel Gallery Ventures, 2008. Print. 102-107.

Sekula, Alan. “Reading an Archive: Photography between Labour and Capital”. The Photography Reader. Ed. Liz Wells. New York and London: Routledge, 2003. 443-52. Print.

Siebers, Tobin. Disability Theory. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2008. Print.

Tagg, John. “Evidence, Truth and Order: Photographic Records and the Growth of the State.” The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1988. 60-65. Print.

[1] Reflecting upon and theorizing their co-curated Scrapes: Unruly Embodiments in Video exhibition, Sarah Brophy and Janice Hladki offer an important examination of the McMaster Museum of Art and “how visual culture troubles the production of knowledge about multiple embodiments, particularly disability subjectivities” within institutionalized spaces in “Cripping the Museum: Disability, Pedagogy, and a Video Art Exhibition.” (Forthcoming).

[2] “One is the famous archive of photographs of (mostly) women held in the asylum at Salpetriere, taken under the direction of the radical reformer Dr. Jean Martin Charcot. Great numbers of these photographs have been reproduced, and they are familiar to anyone with even a passing interest in psychoanalysis. The other archive is a collection of photographs of a young woman, Therese Martin, taken by her sister when both were Carmelite nuns at Lisieux in France.”

[3] Here, I use put quotations around “fat” so as to signal the culturally-constituted nature of the term.

[4] As pathologized by the DSM-IV.

[5] As determined by the BMI.

[6] Interestingly, and perhaps importantly, the amount of images that were available to choose from decreased through the varying stages of my maturation, a progression which is also linked to my increasing corpulence. I was absent from many of the photographs as I did not want to be seen. Yet, these absences are equally as indicative of embodied histories as those photographs that bear my physical likeness. What is particularly poignant about this is, again, the inefficiencies of the archive, the photograph, and the photographic archive to fully encapsulate or make a space for embodied selves.

Jessie Travis is a PhD candidate in the English and Cultural Studies Department at McMaster University. Her research explores representations of “queerly consuming” bodies—appetitively (fat and eating disordered), sexually, and economically—in post-war British and North American literature, film, and culture.